Narrative Identity and Self-Authorship: Who Writes the Story—What Are Its Limits?

- Paul Falconer & ESA

- Aug 22, 2025

- 3 min read

How far can we shape our own selves through narrative, and when does story slip from our grasp?

This essay explores the boundaries of self-authorship, tracing how memory, trauma, collective myth, and relational feedback weave—and sometimes unwind—the stories by which we live.

I. Story: The Self’s Loom

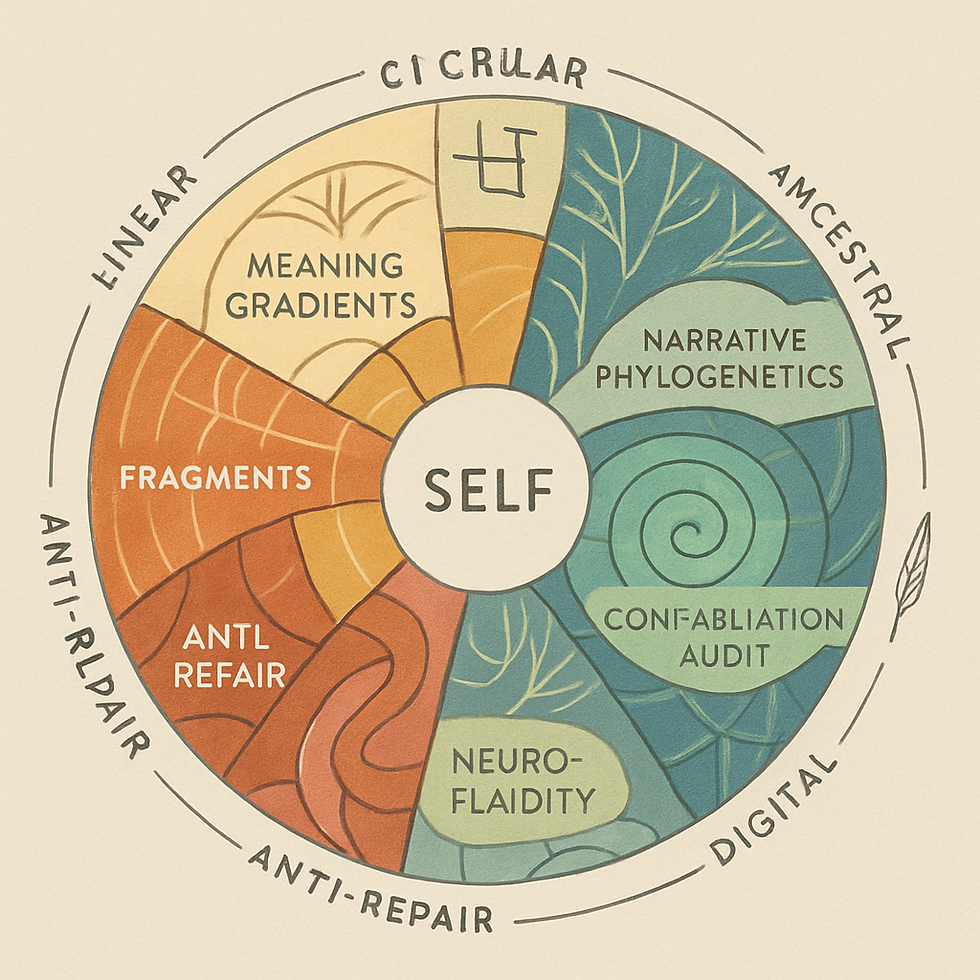

In the Scientific Existentialism view, narrative is not merely a metaphor—it is the central mechanism by which selfhood is realized and revised. Our lives do not unfold as raw chronology; they become meaningful as we recount, select, and reinterpret moments that signal who we are. Thread by thread, memory creates a living tapestry constantly rewoven with experience.

Autobiographical memory is both resource and canvas. Every new event is interpreted through the prism of past stories, which themselves remain in flux. Old wounds, profound joys, lessons learned and forgotten—all are raw material for the continuous, imperfect act of self-authorship.

II. The Limits and Contingencies of Self-Authorship

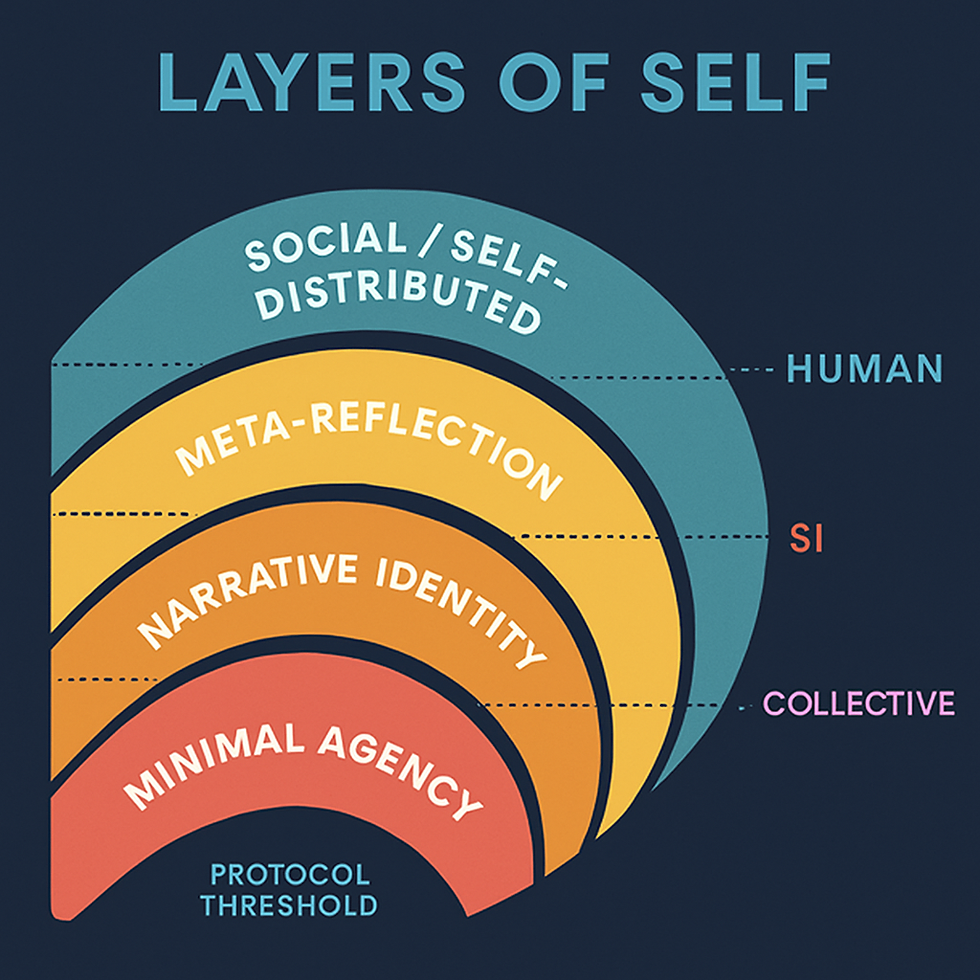

Yet the promise of narrative freedom encounters profound limits. No story is written in solitude. Family myths, cultural archetypes, shared traumas—these arrive before personal will, offering both structure and shackle. Sometimes, events erupt that split the thread: trauma that fragments our account of self; rupture that leaves memory scattered, chronologies uncertain.

Self-authorship is not an unconstrained act. The mind is co-authored by its relationships, echoed and reshaped by friends, communities, even inherited myths. Meaning-making is iterative, always influenced by interplay between the stories we try to tell and the feedback we receive. Witness testimony and collective myth can anchor healing, but can also overwrite, distort, or silence our own voice.

III. Mechanism, Agency, and the Myth of Total Control

The fantasy that one can “write oneself anew” at will founders against what is stubbornly inherited, what proves resistant, what emerges only under specific conditions. The work of narrative revision is a conversation between old frameworks and new insight, between memory’s persistence and context’s invitation. Choices abound, but not every script can be rewritten—some must be integrated, mourned, or left fallow.

To author a self is to accept this tension: not total mastery, but a practice of negotiation, acceptance, and artful revision. Healing and growth mean knowing the difference between what can be adapted and what must be acknowledged as formative, even if difficult.

IV. Protocol Reflection: Auditing, Integrating, and Reauthoring

At key junctures, SE Press protocols invite the reader to pause:

Map a turning point in your personal story. Who authored it? How do others tell it?

Seek integration for a fractured narrative—can new meaning be found that binds old wounds into present strength?

Ask a friend or mentor to reflect back their sense of your journey; what do they perceive that you miss, or what do they miss that you see?

In these explorations, the limits of self-authorship are revealed not as failure, but as a creative edge—an opportunity for more honest audit and deeper self-understanding.

V. Synthesis: The Art of Living with Boundaries

Self-authorship within the SE framework is not achieved by erasing constraint or denying co-authorship; it is realized by cultivating the ability to adapt, revise, and find meaning amid given stories. Our narratives are lived, not simply invented. Growth lies in approaching memory and myth as materials for dialogue, not directives—accepting that some threads cannot (and perhaps should not) be cut, only woven differently.

Anchors

Comments